This week’s Q & A is with the China-born and now Boston-based Xujun Eberlein, a short story writer, blogger, essayist, and contributor to LARB.

I contacted Xujun in part simply because I was curious to learn her reaction to two recent literary-minded and China-focused New York Times pieces. One focused on the surprisingly brisk sales in China of a book by James Joyce, while the other was a commentary by NPR Beijing bureau chief Louisa Lim on trends in censorship and the popularity of Chinese “officialdom novels.” Both brought Xujun to mind, since she has often reflected on the flow of books and ideas between China and the West and she has written an essay on the “officialdom novel” genre.

She was good enough to break up her Lunar New Year trip back to Chongqing to speak with me.

Jeff Wasserstrom: Do you have any thoughts on why Finnegans Wake might be selling so well in China?

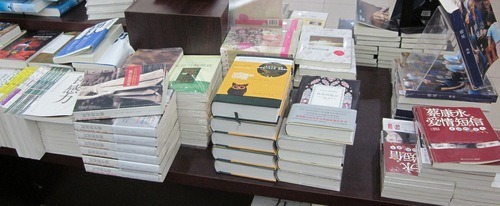

Xujun Eberlein: I was curious about this myself. I’m in Chongqing for Chinese New Year and I went to the Xinhua Bookstore downtown on Saturday (February 9) to have a look at the book. A young staff member led me to the desk where the Chinese translation of Finnegans Wake (the yellow cover at the center of the above photo) was on display with other new and noteworthy books. As you may see from the photo, next to Finnegans Wake is the translation of polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz’s Quo Vadis, which has a supplementary band to note the author is a Nobel Laureate. The red cover on the right is a Chinese popular novel titled Love SMSs. I asked the young man how Finnegans Wake was selling there and he said “Not bad.” He noted that its sales were similar to One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in the Time of Cholera. When asked what kind of readers were buying it, he said “mostly young people.”

Read more.